- Home

- Pamela D. Toler PhD

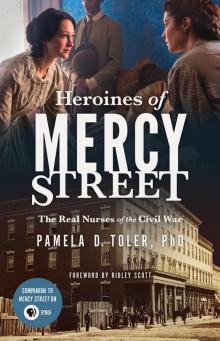

Heroines of Mercy Street Page 8

Heroines of Mercy Street Read online

Page 8

The Sanitary Commission was ready to step into action in July 1861, when the debacle of Bull Run proved the Medical Bureau was unprepared to protect the health of its soldiers. Olmsted, frail and permanently crippled in a carriage accident, personally inspected twenty military camps near Washington. Other male volunteers inspected and reported back to the commission on the condition of the military’s improvised hospitals. The commission built new hospitals using an innovative pavilion design intended to promote air circulation in the wards. Regional branches funneled supplies from local organizations to military hospitals and convalescent camps.

All of these tasks were well within the scope of Bellows’s original proposal to Secretary Cameron. In March 1862, General George McClellan’s Peninsular Campaign presented the Sanitary Commission with a new challenge.

The Peninsular Campaign Begins

In the spring of 1862, General George McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, was under increasing political pressure to take the offensive. President Lincoln had issued General War Order No. 1 on January 27, directing all United States forces to advance against the Confederate army on February 22—George Washington’s birthday, a date chosen for its symbolic significance. McClellan ignored the order. Now both Lincoln and his new secretary of war, Edward Stanton, were proposing an overland advance straight south from Washington against the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia.

McClellan pushed through a more ambitious plan that would allow him to bypass the Confederate army massed at Bull Run. Beginning in mid-March, using a fleet of some four hundred steamboats, he moved more than 100,000 men—along with more than twelve hundred wagons and ambulances, three hundred pieces of artillery, fifteen thousand horses, and countless tons of supplies—south to Fort Monroe, in what would be the largest American amphibious operation prior to the Allied invasion of Normandy in 1944. On April 4, the Army of the Potomac began its advance toward Richmond up the swampy lowlands of the narrow Virginia Peninsula between the York and James rivers.

When McClellan’s forces reached Yorktown, the site of George Washington’s decisive victory over Lord Cornwallis ninety-one years previously, the general mistakenly believed that the Confederate army vastly outnumbered his troops, thanks to poor information from his staff. His intelligence section was staffed by civilian agents provided by the Pinkerton Detective Agency. Pinkerton agents were skilled at capturing counterfeiters and bank robbers, but they were not accustomed to estimating troop strengths from conflicting and erroneous reports, many of them gathered from escaping slaves. The agents consistently overestimated the size of the Confederate forces at two or three times their actual strength. At Yorktown, their reports of the size of the Confederate forces ranged from 40,000 to 100,000 troops; General John G. Magruder originally commanded fewer than 15,000 men at Yorktown. Magruder reinforced Pinkerton’s overassessment of Confederate troop numbers with an elaborate ruse. He ordered logs painted black and placed in temporary fortifications, known as redoubts, to give the appearance of many artillery pieces. (When they were discovered after the Confederate retreat, the press mockingly called them “Quaker guns.”) Magruder then marched his men back and forth between the redoubts. Not much of an illusion, but enough to fool a general who was already convinced that a large Confederate army held the city.

Lincoln urged McClellan to attack. McClellan, increasingly convinced that he faced overwhelming odds, instead chose to besiege Yorktown, giving Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston, one of the victorious commanders at Bull Run, time to reinforce Yorktown with additional men. In early May, McClellan finally attacked. The Confederate forces slipped away in the night on May 4, leaving behind empty trenches and a few landmines—a new and devastating war technology. Finally on the move, McClellan pursued them to Williamsburg, where they fought a savage holding action before the city fell on May 5. On May 15, McClellan set up his headquarters on the muddy little Virginia river known as the Pamunkey. The Union army pushed its way up the river, creating supply bases at strategic spots as they moved forward: Eltham’s Landing, Cumberland Landing, and finally White House Landing, the point where the York River Railroad crossed the Pamunkey.

The Army of the Potomac was ready to advance on the Confederate capital.

The Hospital Transport Service

While McClellan and his quartermaster worked out the details of an amphibious assault on the Virginia Peninsula, the Medical Bureau and the Sanitary Commission considered the consequences of such a strategy on the already overburdened resources of the army’s medical system. In addition to high battle casualties, field hospitals could expect large numbers of ill soldiers thanks to the malarial swamps. The inhospitable terrain of the Virginia peninsula, with its swampy forests and miry roads, would make it difficult to transport wounded and sick men from the battlefield with horse-drawn wagons. The obvious answer was a water-based evacuation system, but the army’s prior effort at hospital transport ships had been a failure. Instead of trying again, the army contracted with the United States Sanitary Commission to operate a semi-independent hospital transport system, using steamships to evacuate wounded and sick soldiers through the James and Pamunkey rivers and then take them up the coast to Northern hospitals. The army quartermaster would provide a fleet of ships to serve as hospital transports; the Sanitary Commission would staff and supply them. Olmsted was put in charge of the program and traveled with the ships over the course of the campaign. On occasion he would allow himself to become involved in the care of soldiers as well as logistics: Georgeanna Woolsey noted in her diary that Olmsted would sometimes slip into a cabin when the ward was quiet and sit on the floor by a dying German “with his arm round his pillow—as nearly round his neck as possible—talking tenderly to him [in German] and slipping away again quietly.”9

The commission received its first steamboat, the Daniel Webster, on April 25, and volunteers spent the next five days scrubbing it clean, installing bunks, and outfitting it for medical use. Over the coming weeks, the commission converted another fourteen ships into floating hospital transports; they included three steamers capable of making the ocean passage from Fort Monroe to New York, and the appropriately named Wilson Small, a shallow-draft boat that could navigate creeks and shallow tributaries and would be used to bring both wounded and nurses downriver to the larger transport vessels. Each ship was staffed by at least one volunteer surgeon, one assistant surgeon, a “lady superintendent,” a ward master, and two nurses for each ward, some of whom, like Anne Reading, were paid nurses rather than volunteers. The line between volunteer and nonvolunteer was always blurry, and occasionally the source of difficult relationships among paid nurses, unpaid nurses, and surgeons. Amy Morris Bradley, for instance, asked by a surgeon whether she was a paid nurse, ranted in her diary, “To think that I, poor Amy Bradley would come out here to work for money and that the paltry sum of twelve dollars per month and Rations!… Thank God I had a higher motive than a high living & a big salary.”10 Medical students worked as volunteer dressers, which meant serving as a physician’s assistant, with special attention to dressing wounds.

The inclusion of female nurses on the ships represented a major change in Sanitary Commission policy. Even though providing a corps of trained women nurses was one of the original missions of the WCAR, the all-male executive board of the Sanitary Commission—faced with continued army resistance to the idea of women in military hospitals and increasingly at odds with Dorothea Dix over questions of jurisdiction—abandoned the idea of training and hiring nurses as early as November 1861. Olmsted, however, had assumed from the beginning that nurses would be part of the hospital transport service. The commission’s goal, as outlined by Olmsted, was to ensure “that every man had a good place to sleep in, and something hot to eat daily, and that the sickest had every essential that could have been given them in their own homes.”11 He envisioned the transport ships as being less like hospitals and more like a home away from home, where an injured soldier could rest and r

ecover in relative ease, complete with women to prepare beds for incoming casualties, staff kitchens to prepare special diets for the ill, and comfort the wounded—replicating the middle-class domestic experience of nursing a family member in an institutional setting.

Olmsted also envisioned the ships as a secure place for middle-class and elite women to serve away from the rough atmosphere of overcrowded military hospitals. For every woman who volunteered as a nurse, another was held back by the disapproval of family, friends, and society’s assumptions about proper behavior for a lady. Some feared ruined reputations as a result of the moral laxity of military hospitals. A friend warned Harriet Whetton that “so much is said about the nurses who have gone. Some of the men say that they are closeted for hours with the surgeons in pantries and all kinds of disorders go on.”12 Other naysayers argued women would lose their femininity through exposure to the coarse realities of hospital nursing, vividly described by an anonymous doctor in a letter to the influential American Medical Times:

Imagine a delicate refined woman assisting a rough soldier to the close-stool, or supplying him with a bed-pan, or adjusting the knots on a T-bandage employed in retaining a catheter in position, or a dozen offices of a like character which one would hesitate long before asking a female nurse to perform, but which are frequently and continually necessary in a military hospital.13

Some feared they would be subject to sexual advances from the soldiers they were there to nurse, an event that seems unlikely given the condition of most of the soldiers described in the letters and memoirs of the nurses themselves. For women who wanted to volunteer but had not been able to stand up against those who discouraged them, the hospital transport ships, under the control of the Sanitary Commission rather than the army’s Medical Bureau, seemed to offer an opportunity to serve away from the dangers of both the battlefield and army hospitals.

Anne Reading was an anomaly among the women who staffed the hospital ships. Olmsted attracted an unusual number of self-described ladies to the transport service, many of them volunteers Dix had previously turned away. He actively recruited New York socialites Eliza Woolsey Howland and her sister Georgeanna Woolsey as lady superintendents before he had even completed his negotiations with the government for ships. Both women had successfully completed Dr. Blackwell’s short-lived nurse training program at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. They reported for duty with less than a day’s notice to serve as lady superintendents when the Sanitary Commission took possession of its first ship, the Daniel Webster, on April 25; they brought with them a trunk filled with towels and old sheets, soap, cologne, oil silk, sponges, a small camp cooking stove, and a spirit lamp. Their first task as lady superintendents was sewing a flag marking the Daniel Webster as a hospital transport, which they did surrounded by the ship’s carpenters and contraband slaves who were making final repairs to the ship. Only after their flag was hoisted did they buckle down to the real work of getting the filthy river steamer into condition to receive patients, a job that took several days of unladylike labor.

“Transport Women” in Action

The hospital transport service plunged into action on May 4, when the Confederate army evacuated Yorktown. Olmsted scrambled to field a team to take care of the sick and wounded left behind. Amy Morris Bradley, who had previously spent eight months as a volunteer field nurse with the Third Maine regiment, arrived at Fort Monroe on May 6. Olmsted met her there and ferried her on the Wilson Small upriver to Yorktown, where she transferred to the Ocean Queen. Anne Reading and her twenty-some traveling companions arrived at Yorktown the next day. Six of them were assigned to the Ocean Queen. Others, including Reading, were put to work on the river steamers.

Yorktown was Reading’s first close view of war in the field, something she was never exposed to in the Crimea. The Confederate forces had evacuated the city in the night with so little notice that men left pork stew and half-baked biscuits on their campfires. The hills were dotted with abandoned baggage and Magruder’s redoubts, with their Quaker guns. The Union troops were preparing to go upriver in full pursuit and the pier “was crowded with men, horses, casks, swords, guns, contrabands, and everything else that was warlike.”14

The hospital transport service was preparing to go upriver as well. The next day Reading was part of a team that traveled in the Wilson Small to West Point, where they picked up twenty-one severely wounded men and brought them back downriver to the Elm City, which would deliver a total of four hundred soldiers to a hospital in Washington. As soon as they had transferred their patients to the Elm City, another steamer pulled up alongside them. Reading and the other nurses had just sat down to tea when Olmsted came on board and said, “Ladies, here is the Knickerbocker with one hundred and fifty men, sick and wounded on board. They have had nothing to eat since the day before yesterday.” The nurses abandoned their own meal without hesitation, and in minutes they were on board the Knickerbocker, tending to hungry and wounded soldiers. Those strong enough to eat got tea with bread and butter. Those too faint were given brandy and water or beef tea as the case required. Once they were fed, the nurses washed them and dressed their wounds; three days later they took on another 150 men and began the process again.15 They then conveyed the men to Washington, attending to their comfort as best they could in the hold or on the deck of the crowded Wilson Small.

The routine never ended. Nurses brought a batch of soldiers on board, cared for them, in some cases became attached to them—an emotion that appears to have been generally more maternal than romantic—then turned them over to nurses on the next stage of their voyage, and steamed back upriver to begin the cycle again.

While they were on the transport ships, the nurses were both in the center of the war and distant from it. The flow of damaged bodies was seemingly unending, but news about the course of the war arrived at a less dependable rate. Seldom interrupted by references to the larger action of the war, there is a numbing monotony to their accounts of traveling back and forth on the Pamunkey River between Fort Monroe and the Harrison and White House landings. Katherine Wormeley estimated that her team recovered, treated, and transported almost four thousand men in one three-day period at the height of the campaign.16

The occasional adventure broke up the ship’s tedium. In one incident Reading and her companions left the ship and took a small tug upstream to search for a group of men rumored to be lying farther upriver with no one to help them. On another occasion, Reading was thrilled to be introduced to General McClellan, who was told she had been a nurse in the Crimean War. She received a hearty handshake from “Little Mac,” and thanks “that an Englishwoman would render them a service in such a time of need.”17 But such moments were rare. The most common excitement occurred when the army confiscated ships without warning to use as troop transports; nurses grew accustomed to scrambling from one ship to another with only a few minutes to prepare. For the most part, the action of the war remained at a distance while the nurses dealt with its heartbreaking effects.

At the end of June, the Seven Days’ Battles reversed the momentum of the campaign. Despite McClellan’s cautious nature, his troops had advanced steadily toward Richmond. Now Lee pushed back. McClellan’s forces outnumbered Lee’s by almost two to one, but the Confederate general forced McClellan first to abandon the supply line at White House Landing and then to retreat with the Confederate army in pursuit. Suddenly the hospital transportation service was plunged into the middle of the war. Gunboats lined the shores of the river. The fleet worked around the clock to ferry the sick and wounded from the Harrison and White House landings to Yorktown or Fort Monroe, with a protective convoy. In addition to removing wounded soldiers, the transport ships also removed as many stores as possible from the supply depots. Each steamer towed store ships behind them: Reading’s ship towed twelve supply-laden schooners away from White House Landing. But they did not have enough time to take everything. As Reading’s ship left, soldiers were burning the supplies they left behind

so there would be nothing for the Confederates to take possession of. As Reading noted in her journal, “Thus we left that once beautiful place, the White House at the head of the Pamunkey River, blackened and charred, a blazing head of ruins.”18

On July 27, Reading took part in her first exchange of wounded prisoners. Her ship received orders to hoist a white truce flag alongside its hospital flag and travel in a guarded convoy to City Point; there they would take on wounded soldiers who had been taken prisoner in the retreat from White House Landing, and were now being exchanged for Confederate prisoners. The convoy of ships arrived shortly after the Confederate train reached the station at City Point. Reading was saddened by the sight of the remains of the formerly pretty town and noted that those living in the peace and comfort of England could have no idea of the misery endured by those living in the midst of the war. She found it strange to see “our men being led or carried by the rebel guard from the [train] cars to the steamer with as much care and tenderness as if they were brothers.”19

It was difficult to believe these same men had been engaged in deadly combat with each other only days before.

Life on the Ships

The Sanitary Commission promised its nurses, and perhaps more importantly their families, that service on the transport ships would be a sheltered experience. In reality, the nurses on the transport ships were closer to the battlefield than their counterparts in the military hospitals and saw some of the worst scenes of suffering of the war. Even Bradley, who had already seen more battle injuries than any other nurse in the hospital transport service, before becoming the atypical lady superintendent of the Knickerbocker, found herself unprepared for the condition of the wounded brought by train to White House Landing after the Battle of Fair Oaks (known as the Battle of Seven Pines in the South) on May 31. She was overwhelmed by emotion as she watched the mutilated soldiers carried on board on stretchers and carefully placed on the cots she had prepared for them. For nearly an hour she struggled to control her feelings, weeping and protesting, “Must I see human beings thus mangled? O, My God, why is it? Why is it?” She finally pulled herself together after the surgeon admonished her: “Miss Bradley, you must not do so, but prepare to assist these poor fellows.” Ashamed of herself for losing her focus, she choked back her tears and told herself, “Action is the watchword of the hour!”20 Many women returned home after their first look at the condition of the men aboard the ships. Those who remained worked harder than they had ever worked before.

Heroines of Mercy Street

Heroines of Mercy Street